1990 Much of the interest in Indian traditions in recent years has been coming from Indians themselves, who are rediscovering their culture roots.

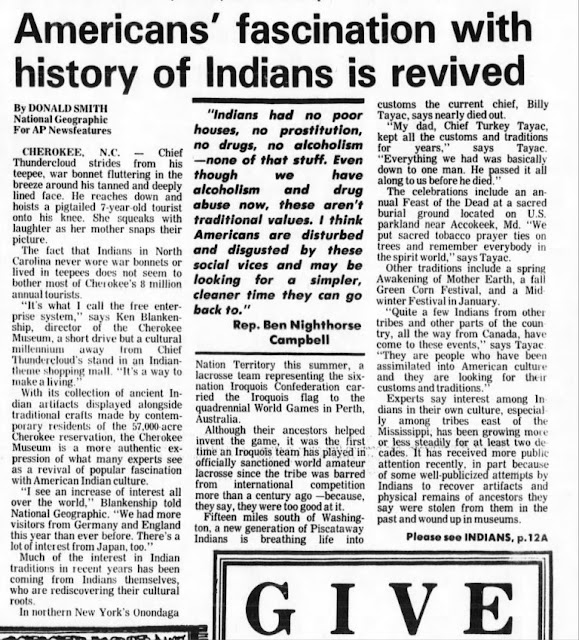

Americans' fascination with

history of Indians is revived

by Donald Smith

1990 Oct 21, The Star Democrat

Cherokee, NC - Chief Thundercloud strides from his teepee, war bonnet fluttering in the breeze around his tanned and deeply lined face. He reaches down and hoists a pigtailed 7-year-old tourist onto his knee. She squeaks with laughter as her mother snaps their picture.

The fact that Indians in North Carolina never wore war bonnets or lived in teepees does not seem to bother most of Cherokee's 8 million annual tourists.

"It's what I call the free enterprise system," says Ken Blankenship, director of the Cherokee Museum, a short drive but a cultural millennium away from Chief Thundercloud's stand in an Indian-theme shopping mall. "It's a way to make a living."

With its collection of ancient Indian artifacts displayed alongside traditional crafts made by contemporary residents of the 57,000 acre Cherokee reservation, the Cherokee Museum is more authentic expression of what many experts see as a revival of popular fascination with American Indian culture.

“I see an increase of interest all over the world,” Blankenship told National Geographic. “We had more visitors from Germany, and England this year than ever before. There’s a lot of interest from Japan, too.”

Much of the interest in Indian traditions in recent years has been coming from Indians themselves, who are rediscovering their culture roots.

In northern New York’s Onondaga Nation Territory this summer, a lacrosse team representing the six-nation Iroquois Confederation carried the Iroquois flag to the quadrennial World Games in Perth, Australia.

Although their ancestors helped invent the game, it was the first time an Iroquois team has played in officially sanctioned world amateur lacrosse since the tribe was barred from international competition more than a century ago – because, they say, they were too good at it.

Fifteen miles south of Washington, a new generation of Piscataway Indians is breathing life into customs the current chief, Billy Tayac, says nearly died out.

“My dad, Chief Turkey Tayac, kept all the customs and traditions for years,” says Tayac. “Everything we had was basically down to one man. He passed it all along to use before he died.”

The celebrations include an annual Feast of the Dead at a sacred burial ground located on US parkland near Accokeek, Md. “We put sacred tobacco prayer ties on trees and remember everybody in the spirit world,” says Tayac.

Other traditions include a spring Awakening of Mother Earth, a fall Green Corn Festival and a Mid winter Festival in January.

“Quite a few Indians from other tribes and other parts of the country, all the way from Canada, have come to these events,” says Tayac. “They are people who have been assimilated into American culture and they are looking for their customs and traditions.”

Experts say interest among Indians in their own culture, especially among tribes east of the Mississippi, has been growing more or less steadily for at least two decades. It has received more public attention recently, in part because of some well-publicized attempts by Indians to recover artifacts and physical remains of ancestors they say were stolen from them in the past and wound up in museums.

Now, Indian scholars and tribal leaders are participating in Smithsonian Institution plans for a new National Museum of the American Indian. At an estimated construction cost of $100 million, the museum would occupy a prominent site alongside other Smithsonian buildings on the Mall between the Washington Monument and the US Capitol.

“The Western tribes never had a big period of rediscovery, since their culture was never completely stamped out,” says Rose Robinson of the National Congress of American Indians in Washington. “But the eastern groups lost a great deal of their own traditions. That’s why you see some Western Indian styles and forms of religion being picked up in the East in recent years.”

Mrs. Robinson, a Hopi, says many Indian groups lost their cultural bearings through years of urbanization and assimilation in Anglo-European ways.

Rep. Ben Nighthorse Campbell, D-Col, the only American Indian serving in the US Congress, thinks Americans may be captivated by an idealized vision of Indian society before European contact.

“Indians had no poor houses, no prostitution, no drugs, no alcoholism – none of that stuff,” he says. “Even though we have alcoholism and drug abuse now, these aren’t traditional values. I think Americans are disturbed and disgusted by these social vices and may be looking for a simpler, cleaner time they can go back to.”

|

| 1990 Oct 21, The Star Democrat |

Comments

Post a Comment