1981 Russell Means / hero or villain?

Russell Means/ hero or villain?

By Chuck Raasch

1981 Nov 1, Argus Leader

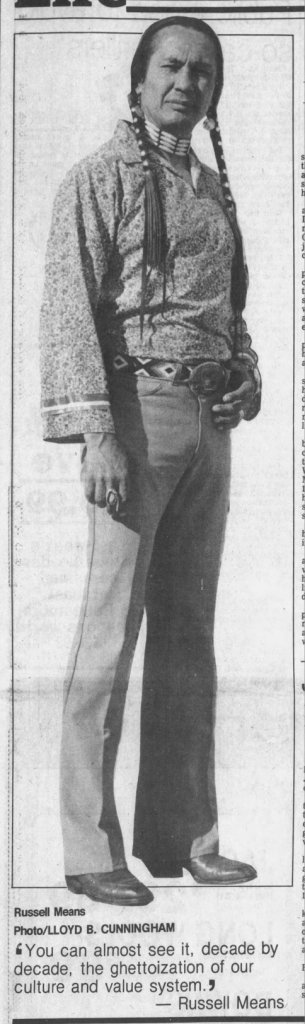

Posing mutely for the camera, he looks imposing: His face is defiant, his shoulders thrown back as proud platforms for spirals of braided hair.

But strip away the publicity veneer and Russell Means smiles easily and speaks softly and thoughtfully. He exudes the humility of a man approaching middle age, a man who has seen some of his goals swept away by the conflicts of humanity.

These days, he talks less about confrontation and more about setting an example for fellow Indians. Some who know him see this as a mellowing with age; he will turn 42 on Nov. 10. Others believe the new style is a reaction to his jail time in the late 1970s and the manslaughter conviction of his son, Hank, this summer.

He is a hero to Indian activists and white sympathizers, but a villain to those who think his confrontationist tactics have harmed race relations in South Dakota. His public rhetoric is sometimes ambiguous, too: Means condemns white man’s assault on his people’s culture and advocates a return to traditional ways, but travels the world by jet to promote his cause.

But friends and associates say his public and private styles are not fakes and that in every human being, in every cause, there are enigmas and complexities.

Means is not a violent man by nature, they say, but a gentle family man deeply disturbed by his son’s manslaughter conviction over the death of a Rapid City Catholic priest during a robbery attempt. Neither, they day, is he a con man simply fantasizing about an Indian way of life that was gone a century ago.

“I think Russ has been about very serious business, despite the fact that people call him a clown… or they call him this or they call him that,” says the Rev. John P. Adams, a Fort Wayne, Ind, Methodist minister who has known Means since the Wounded Knee occupation of 1973. “I think he’s realized that somebody has had to play the role he’s had to play. Although some think he’s in it for personal gain, I’ve never seen that much gain for him.”

The role? Perhaps more than anything, Means has brought the cause of the American Indian into an international domain.

AJIM leaders grieve before the United Nations and before human rights commissions in Geneva, Switzerland. Several years ago, Adams says he met with Australian aborigines who had AIM literature and Means posters. AIM has drummed up interest in Germany and France.

“There are people in those nations who see our problems with Native Americans that we’re almost blind to,” Adams says. “We somehow look at it as something in the past, as something we’ve taken care of.”

If Means has his way, there will be no forgetting. The problems of Indians are the same as before 1967, when AIM was formed, he says. But then, he says, Indian people were safely out of sight and out of mind.

It’s been less than a decade since Means engaged in his first major confrontation. But the message hasn’t changed much in the past 10 years. White man’s government and society is sweeping the Indian culture and heritage away against the Indians’ will, he says. The process leaves a generation of confused young Indians, as well as whites who often react to Indians out of fear and ignorance.

“You can almost see it, decade by decade, the ghettoization of our culture and value system,” Means says.

But the old days of confrontation for confrontation’s sake seem to be changing. As a member of the Yellow Thunder Camp in the Black Hills, Means says he is now acting through spiritual prodding’s. The Yellow Thunder Camp campers want to be self-sufficient by 1984 and, he hopes, a positive example for other Indian people who want to maintain cultural identity.

“Previous AIM actions were politically and/or legally motivated,” Means says, drawing hard on a cigarette and pausing in thought. “This is entirely spiritually and culturally motivated.”

However, he says, the camp “can only be an example. We in no way can ever take upon the responsibilities of the entire Lakota Nation.”

Whether the camp will receive permanent blessings from the government isn’t clear yet. But Means says Yellow Thunder is for real, and it will prove so by surviving the winter.

“What we want at Yellow Thunder is a cultural and physical leave us along policy,” he says. “Just let us be Indians. What’s wrong with being Indians? I mean, total Indians, where we have respect for our mother and grandmother earth, and everything is sacred and Holy. And (where) you do not rape and murder and colonize and turn around and call it development and progress.”

For those whose remember Means only through the violent residue of the 1970s, that is soft talk.

It started in 1972, when Means helped organize a protest over the public humiliation and death of Raymond Yellow Thunder (namesake of the Black Hills camp) at Gordon, Neb. Later, Means lead the 71-day occupation of Wounded Knee in 1973. The Minnehaha County Courthouse riots followed. He was involved in a barroom brawl at the Mission Country Club.

Within the span of 10 short years, Means was stabbed, show in the chest and stomach; he beat a murder charge, then did time at the State Penitentiary for inciting a riot during the Minnehahah County Courthouse melee.

He was shown in newspapers in handcuffs and bare-chested with a bandage on his chest after a prison stab wound. Always tough. Always defiant.

“We have had no way to express our manhood on the reservation except for five ways,” Means told a crowded courtroom when the AIM trails began Feb 12, 1974. “Those five ways are athletics, joining the service, grabbing the bottle, beating our women, or cutting our hair, putting on a tie and becoming a facsimile of white people.”

The confrontationist image has not been an easy badge to wear in South Dakota, a state still beset by century-old racial problems between white and Indians.

Penitentiary Warden Herman Solem says Means avoids bars now because it’s been fashionable among some to claim they have fought and beaten Russell Means.

“Any time a fourth class citizen tries to raise to first class status, there is going to be conflict and confrontation,” Means says.

But that role has gotten him condemned, too.

Gov. William Janklow, a former friend but now a public opponent, says Means is a bright and articulate man who has wasted much of his life because of the violence he has encouraged. Some of Means’ biggest enemies have been members of his own race, such as former Pine Ridge Tribal Chairman Dick Wilson.

While not condoning violence, Adams became a friend after meeting Means at the Wounded Knee siege 81/2 years ago. As a former director of the Methodists’ national Law, Justice and Community Relations group, Adams has often tried to settle AIM-government disputes behind the scenes, and is recognized by both sides as a fair and impartial mediator.

“When people call them (AIM leaders) clowns, I usually like to remember what Emmett Kelley (a famous circus clown) once said about a clown,” Adams says. “He said that being a clown means that when you act you have to act out in an exaggerated way to gain attention because of the competition of the three rings in the circus. In a highly competitive socio-drama, they’ve (AIM) had to exaggerate their role.”

Others say the public image that Means is less than sincere troubles him.

“In my estimation, he is certainly continuing in his commitment to what he’s doing,” John Garvey, Catholic priest in Platte who has known Means for seven years, says, “I don’t see any change there except maybe the commitment gets stronger.”

Solemn says Means sometimes covers up a superficial knowledge of certain topics by eloquent language, but that he believes Means is committed to his cause because he has stayed with it so long…….

By Chuck Raasch

1981 Nov 1, Argus Leader

Posing mutely for the camera, he looks imposing: His face is defiant, his shoulders thrown back as proud platforms for spirals of braided hair.

But strip away the publicity veneer and Russell Means smiles easily and speaks softly and thoughtfully. He exudes the humility of a man approaching middle age, a man who has seen some of his goals swept away by the conflicts of humanity.

These days, he talks less about confrontation and more about setting an example for fellow Indians. Some who know him see this as a mellowing with age; he will turn 42 on Nov. 10. Others believe the new style is a reaction to his jail time in the late 1970s and the manslaughter conviction of his son, Hank, this summer.

He is a hero to Indian activists and white sympathizers, but a villain to those who think his confrontationist tactics have harmed race relations in South Dakota. His public rhetoric is sometimes ambiguous, too: Means condemns white man’s assault on his people’s culture and advocates a return to traditional ways, but travels the world by jet to promote his cause.

But friends and associates say his public and private styles are not fakes and that in every human being, in every cause, there are enigmas and complexities.

Means is not a violent man by nature, they say, but a gentle family man deeply disturbed by his son’s manslaughter conviction over the death of a Rapid City Catholic priest during a robbery attempt. Neither, they day, is he a con man simply fantasizing about an Indian way of life that was gone a century ago.

“I think Russ has been about very serious business, despite the fact that people call him a clown… or they call him this or they call him that,” says the Rev. John P. Adams, a Fort Wayne, Ind, Methodist minister who has known Means since the Wounded Knee occupation of 1973. “I think he’s realized that somebody has had to play the role he’s had to play. Although some think he’s in it for personal gain, I’ve never seen that much gain for him.”

The role? Perhaps more than anything, Means has brought the cause of the American Indian into an international domain.

AJIM leaders grieve before the United Nations and before human rights commissions in Geneva, Switzerland. Several years ago, Adams says he met with Australian aborigines who had AIM literature and Means posters. AIM has drummed up interest in Germany and France.

“There are people in those nations who see our problems with Native Americans that we’re almost blind to,” Adams says. “We somehow look at it as something in the past, as something we’ve taken care of.”

If Means has his way, there will be no forgetting. The problems of Indians are the same as before 1967, when AIM was formed, he says. But then, he says, Indian people were safely out of sight and out of mind.

It’s been less than a decade since Means engaged in his first major confrontation. But the message hasn’t changed much in the past 10 years. White man’s government and society is sweeping the Indian culture and heritage away against the Indians’ will, he says. The process leaves a generation of confused young Indians, as well as whites who often react to Indians out of fear and ignorance.

“You can almost see it, decade by decade, the ghettoization of our culture and value system,” Means says.

But the old days of confrontation for confrontation’s sake seem to be changing. As a member of the Yellow Thunder Camp in the Black Hills, Means says he is now acting through spiritual prodding’s. The Yellow Thunder Camp campers want to be self-sufficient by 1984 and, he hopes, a positive example for other Indian people who want to maintain cultural identity.

“Previous AIM actions were politically and/or legally motivated,” Means says, drawing hard on a cigarette and pausing in thought. “This is entirely spiritually and culturally motivated.”

However, he says, the camp “can only be an example. We in no way can ever take upon the responsibilities of the entire Lakota Nation.”

Whether the camp will receive permanent blessings from the government isn’t clear yet. But Means says Yellow Thunder is for real, and it will prove so by surviving the winter.

“What we want at Yellow Thunder is a cultural and physical leave us along policy,” he says. “Just let us be Indians. What’s wrong with being Indians? I mean, total Indians, where we have respect for our mother and grandmother earth, and everything is sacred and Holy. And (where) you do not rape and murder and colonize and turn around and call it development and progress.”

For those whose remember Means only through the violent residue of the 1970s, that is soft talk.

It started in 1972, when Means helped organize a protest over the public humiliation and death of Raymond Yellow Thunder (namesake of the Black Hills camp) at Gordon, Neb. Later, Means lead the 71-day occupation of Wounded Knee in 1973. The Minnehaha County Courthouse riots followed. He was involved in a barroom brawl at the Mission Country Club.

Within the span of 10 short years, Means was stabbed, show in the chest and stomach; he beat a murder charge, then did time at the State Penitentiary for inciting a riot during the Minnehahah County Courthouse melee.

He was shown in newspapers in handcuffs and bare-chested with a bandage on his chest after a prison stab wound. Always tough. Always defiant.

“We have had no way to express our manhood on the reservation except for five ways,” Means told a crowded courtroom when the AIM trails began Feb 12, 1974. “Those five ways are athletics, joining the service, grabbing the bottle, beating our women, or cutting our hair, putting on a tie and becoming a facsimile of white people.”

The confrontationist image has not been an easy badge to wear in South Dakota, a state still beset by century-old racial problems between white and Indians.

Penitentiary Warden Herman Solem says Means avoids bars now because it’s been fashionable among some to claim they have fought and beaten Russell Means.

“Any time a fourth class citizen tries to raise to first class status, there is going to be conflict and confrontation,” Means says.

But that role has gotten him condemned, too.

Gov. William Janklow, a former friend but now a public opponent, says Means is a bright and articulate man who has wasted much of his life because of the violence he has encouraged. Some of Means’ biggest enemies have been members of his own race, such as former Pine Ridge Tribal Chairman Dick Wilson.

While not condoning violence, Adams became a friend after meeting Means at the Wounded Knee siege 81/2 years ago. As a former director of the Methodists’ national Law, Justice and Community Relations group, Adams has often tried to settle AIM-government disputes behind the scenes, and is recognized by both sides as a fair and impartial mediator.

“When people call them (AIM leaders) clowns, I usually like to remember what Emmett Kelley (a famous circus clown) once said about a clown,” Adams says. “He said that being a clown means that when you act you have to act out in an exaggerated way to gain attention because of the competition of the three rings in the circus. In a highly competitive socio-drama, they’ve (AIM) had to exaggerate their role.”

Others say the public image that Means is less than sincere troubles him.

“In my estimation, he is certainly continuing in his commitment to what he’s doing,” John Garvey, Catholic priest in Platte who has known Means for seven years, says, “I don’t see any change there except maybe the commitment gets stronger.”

Solemn says Means sometimes covers up a superficial knowledge of certain topics by eloquent language, but that he believes Means is committed to his cause because he has stayed with it so long…….

|

| 1981 Nov 1, Argus Leader |

|

| 1981 Nov 1, Argus Leader |

Comments

Post a Comment